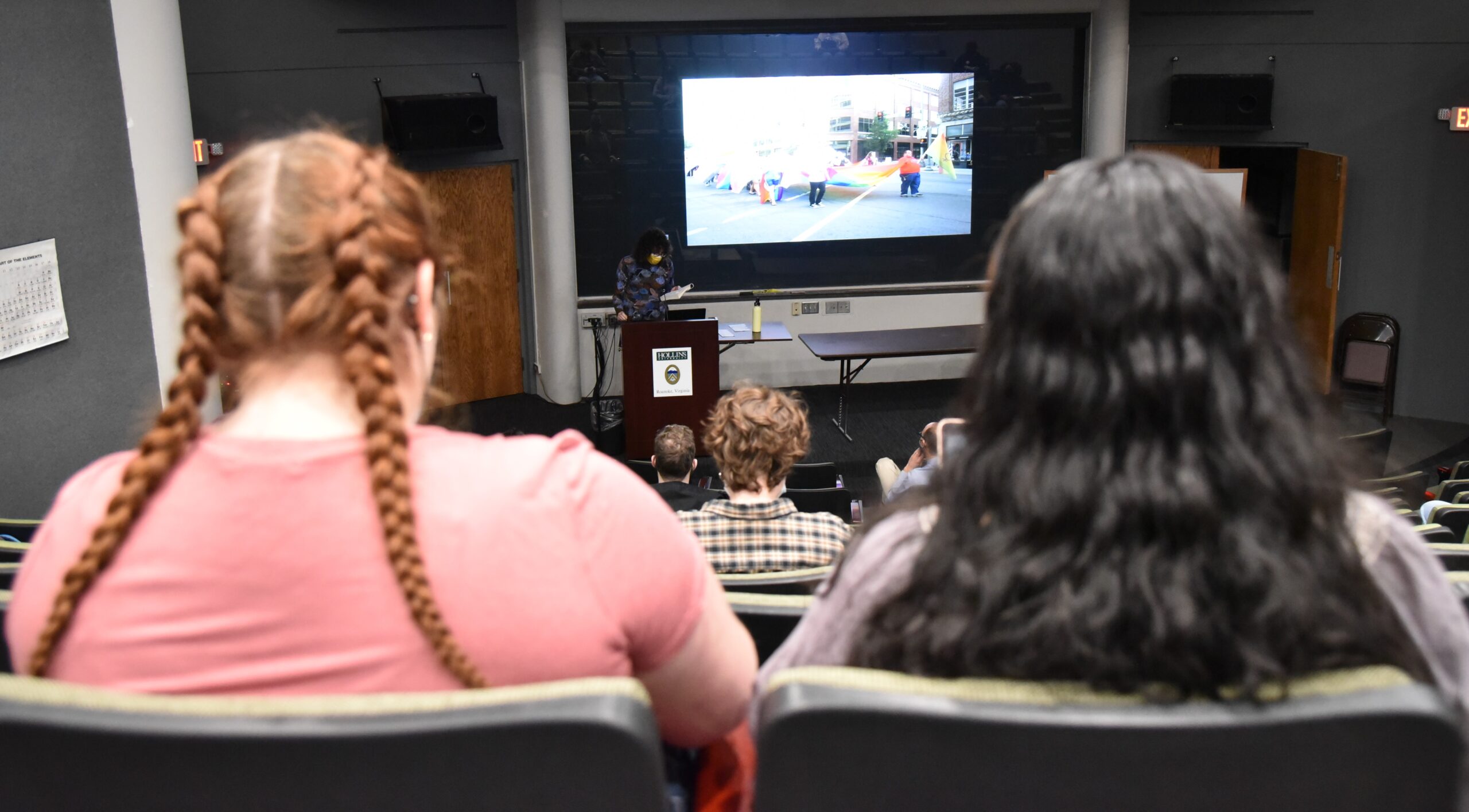

Hollins students, faculty, staff, alumnae/i, and board of trustee members worked toward creating a more equitable and just campus community during the university’s second annual Leading Equity, Diversity, and Justice (EDJ) Conference, held February 24-25.

Over 400 attendees participated in 37 virtual and in-person sessions united around this year’s theme of “Equity, Accessibility, and Identity.” Session topics ranged from “Broaching: Confronting the Uncomfortable Conversations in Systemic Racism” and “Examining Residential Segregation: Where You Live Determines Your Health and Quality of Life” to “Talking Back to Dad: Developing Pedagogies to Discussing Hard Questions in the Classroom and Community” and “Cultivating Inclusive Friendships: Real Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Starts in Our Social Circles.” Session leaders included current students and faculty as well as alumnae/i and guest activists and experts from the community at large.

In her welcome, President Mary Dana Hinton acknowledged that Leading EDJ would be “an emotional and at times difficult day as we share hard truths and have our beliefs challenged. But in those moments, I hope that you will feel pride that this community shows up for one another. I hope you will feel the love that manifests from our willingness to be vulnerable with each other. I also hope that you will have positive emotion today, because even though the work is hard, it’s hard only because we care so much for one another and this institution. It’s hard because we know we need to and want to do and be better. So, in the panoply of emotions on this day, I hope you will allow yourself to experience being seen and heard, and to also feel gratitude and joy.”

Loretta Ross, a nationally recognized expert on racism and racial justice, women’s rights, and human rights, delivered the conference’s keynote address, “Calling In the Calling Out Culture.” Drawing upon 50 years of activism, Ross stressed the need to “create a culture shift” that consciously and deliberately moves away from “publicly shaming or blaming people for something that you think they have done wrong, for which you think they should be held accountable” to a process where “you extend to people love, respect, forgiveness, and grace. Generally speaking, imposing punishments doesn’t achieve accountability because it first of all makes people not want to accept your right to punish them. Second, rarely do they change their minds from their positions or perspectives.”

Ross asserted that advancing human rights “is not a woke competition. It is a movement designed to end oppression. We’re many different people with many different thoughts, but they move in the same direction. That’s a movement. But when many different people think one thought and move in the same direction, that’s a cult. And we are not building a human rights cult.”

In the calling out climate, Ross stated, “people use their knowledge as a weapon against each other because they want to shame somebody for not knowing what they know, whether it’s the latest word that they want to use, or the way that word has become outdated, or whether or not we can remember somebody’s proper gender pronoun. When we weaponize our knowledge, we’re actually demonstrating our own political immaturity.” The result, she added, is that people are discouraged from joining the human rights movement. “It frightens them. They don’t want to speak up for fear that they are going to be the next target if they give voice to an unfinished thought or use the wrong word.”

Ross noted that there are times when calling someone out can be the appropriate action. “The human rights movement uses call outs to hold accountable corporations, countries, and individuals who violate people’s human rights. Sometimes privately getting people to stop their abuses doesn’t work. We have to publicly call them out, because if we don’t, we’ll increase the harm that people experience. The call outs are also very useful for bringing forward those voices that have been historically silenced. Certainly, it works to release that pent-up outrage so that you don’t internalize the anger. You externalize toward the people that are causing the harm.”

Nevertheless, Ross cautioned against the “gotcha” moment “where we unearth mistakes from someone’s past without seeking clarification. This requires seeing people as human beings who make mistakes. We’re not perfect. We’re supposed to make mistakes and then learn from them. When you don’t accept that, you’re devaluing people’s lived experiences as if what you’ve been through is the only truth that matters. This all stems from the concept of toxic perfectionism, where we alienate people with our pursuit of political purity and correctness by assuming there’s only one right way to do something. Or, believing that our job is to take away someone else’s pain by being their advocate – the savior complex. Instead of helping people find their own voices and perspectives, you want to provide it for them.”

Ross shared some simple steps to follow if you yourself are called out. “You can tell the person, number one, thank you. The reason you say thank you is that this person, even if they’re trying to correct you, are gifting you with their time and attention, which are hot commodities right now.

“The second step is to say, ‘I hear you, I appreciate you giving me your perspective, and I’m going to think about it.’ You’ve shown the person that they were heard and respected, but at the same time you have not indicated that you are agreeing with them. You are going to consider it. You maintain your own boundaries and your own dignity.

“Third, flip the script and say, ‘I want to know what’s going on with you, because I care about you the way you care about me. And since I care about you, I want to know why you came at me that way.’ With that, you’ve turned a call out into a call in. You’ve invited them to tell you more.”

Ross concluded her address by reminding the audience that “calling in requires a growth mindset that starts with a self-assessment. You have to analyze how you feel and why you think it’s important to call somebody in or out. If you’re not in a healed enough space for a difficult conversation, you will not be productive. Your own healing should be your number one priority. Calling people in is not an obligation, nor is it a way to paper over the harm that people do. You’re not letting people get away with anything. You’re choosing to use an accountability process that has an increased likelihood of success.”

The 2022 Leading EDJ Conference closed with the Hollins community joining in a virtual gathering for reflections on the day’s experiences, which could then be shared online. One participant wrote, “…lots of interesting information and lots of opportunity to have an impact both locally and beyond,” while another commented, “I have enjoyed this…so much! Each moment and story shared has been so true. I appreciate each voice and feel so inspired.”